Forward, a startup that wants to position itself as the Apple Store of doctors’ offices, opened a new location in Los Angeles in November, in an upscale open-air mall two doors down from an actual Apple Store. On a recent morning, in Forward’s reception lounge (sharp angles, blond-wood walls, soothing blue chairs), devices for at-home monitoring of vital signs were arrayed in a glass case. A body scanner reminiscent of the “Star Trek” transporter stood in a corner. Visitors were greeted by a smiling receptionist’s query: “Flat or sparkling?”

Founded by former employees of Google and Uber, Forward is a concierge medical service that soups up the annual exam with artificial intelligence and a sleek Silicon Valley veneer. Its first office opened last year, in San Francisco; more are planned for 2018. Like a gym or Netflix, or competing primary-care providers like One Medical, Forward charges a flat monthly fee of a hundred and forty-nine dollars, no matter the medical history of its “members”—“ ‘patients’ feels a little paternalistic to me,” Adrian Aoun, Forward’s thirty-four-year-old C.E.O., told me. The service is intended as a supplement to a health-insurance plan, not a substitute. “There are some people that use this as a replacement,” he said. “We strongly don’t recommend it.”

Aoun, who wore a gray T-shirt and an Apple Watch, has an amiable, no-nonsense air. Prior to starting Forward, he built Wavii, a company that created language-processing software. Google bought it for a reported thirty million dollars, in 2013. (Neither Aoun nor Google confirmed the figure.) Aoun worked for a while in Google’s special-projects division (“Larry roped me into it,” he said, referring to Google’s co-founder Larry Page), but he worried about his health. His grandfather died of a heart attack before Aoun was born; his older brother suffered a heart attack at thirty-one. “In the tech industry, we’re pretty used to not accepting the status quo,” he said. The status quo, in his mind, was doctor’s offices, with their myriad inefficiencies and unpleasantries. Aoun figured that if he could bring the Silicon Valley bag of tricks to bear on the traditional medical exam—A.I., technology, proprietary gadgets, open and shareable data—he could remake the way patients take control of their health. It’s one of many ways in which the tech world is seeking inroads into medicine, and a proposition that has reportedly raised a hundred million dollars of investment, including from the former Google C.E.O. Eric Schmidt. (Aoun declined to confirm the fund-raising amount.)

To build the doctor’s office of the future, start with foam and two-by-fours. A year and a half ago, Aoun and his three co-founders leased a warehouse in San Francisco and built a homemade prototype where doctors could test-see patients. (They were still called “patients” back then.) “We just kind of iterated and iterated,” he said. They came up with a “body scanner” that measures height, weight, and body temperature in forty-five seconds, and uses “red-light spectroscopy” to unearth fun facts about the heart. (My resting heart rate was sixty-two beats a minute and my blood was a hundred-per-cent oxygenated.)

The gee-whiz factor is on further display in Forward’s exam rooms, where a six-foot-long flat-screen monitor supplants the doctor’s clipboard. The monitor is hooked up to a natural-language-processing system similar to the one Aoun sold to Google, or to Amazon’s Alexa. “As you and your doctor are speaking, the system is following along and taking notes for you,” Aoun said, though the M.D. can overwrite the machine’s recommendations, “kind of like autocorrect on your phone.” Even exam-room attire proved ripe for disruption. “You know how they put you in that paper smock with your butt hanging out?” Aoun said. “Not classy.” Instead, the company swaths members in Lululemon and other athleisure apparel. After an exam, all data collected—cholesterol numbers, glucose levels, doctor’s notes—get downloaded to Forward’s smartphone app, where members’ full medical profiles sit on their phones alongside Tinder profiles and Seamless orders.

Very few studies have been done about the impact of A.I. on health care, let alone the impact of smartphone apps. Can high-tech flourishes really overcome perennial doctor challenges like poor patient compliance? “Using a fancy, sleek thing to check your weight instead of stepping on a scale, that’s nice, but I don’t know whether it makes a difference,” Dr. Mitesh Patel, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School who researches the impact of wearable devices on health outcomes, told me by phone. “The patients who really need these reminders, the patients who really need to be motivated, are not the patients who are going to join this service. The people who have low motivation don’t go. It’s a Catch-22.”

The Forward team wants medicine to be more like Apple but also more like Facebook, with open and shareable data fostering dialogue between doctors and members. A patient who is inclined to lie about his diet will be kept honest by on-site cholesterol testing. An insomniac will leave Forward with a sensor that tracks her quality of sleep and sends data back to the app. At the very least, she’ll have nifty stats to share on social media. “We had a member post his HDL cholesterol on Instagram,” Aoun said proudly, pulling up the post on his phone.

Imagining the doctors of the Forward future, freed from tedious procedures and jammed fax machines, Aoun offered an analogy: “You know when you’rechecking in at the airport, and the person is typing four thousand characters on a computer, and you look at their screen and it’s black with green characters, and you’re, like, ‘Oh, my God, this isn’t even Windows, this is before Windows’? You start to realize, this person must have an awful life. That’s why they’re grumpy all day. The software made for doctors looks like that. I mean, it is bad. Would you rather use that or use this?” He pointed to the exam room’s six-foot monitor.

On the company’s Web site on the day of my visit, Forward’s offices boasted wait times of one to two minutes. Aoun said that most members don’t actually wait at all. “We couldn’t put zero, that just would’ve been odd.” What about the inevitable person who’s stuck in traffic? “We’re constantly trying to predict, ‘What is the likelihood this person is going to be late and can we adjust schedules accordingly?’ ” he said. “We don’t enable location tracking, but at some point the app will dynamically know where you are and know you’re not on time.”

Or, based on prior history, perhaps Forward’s staff could even determine that a certain member is predisposed to being ten minutes late? “Oh, yeah,” Aoun said. “Easily.”

Recent News

April 22, 2024

March 19, 2024

February 28, 2024

February 22, 2024 | Conversations on Health Care

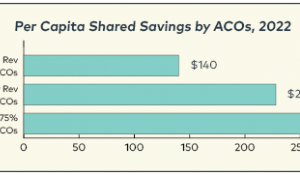

Missed our May webinar, “The Commercial Market: Alternative Payment Models for Primary Care,” check out this clip!… https://t.co/mDZH3IINXK —

10 months 2 weeks ago

Did you catch @CMSinnovates' new #primarycare strategy? Thanks to concerted efforts from @NAACOSnews and other memb… https://t.co/mDnawqw8YW —

10 months 2 weeks ago

Not up to date on the #Medicaid Access and #Managedcare proposed rules important for #primarycare? No worries,… https://t.co/qB6sY3XCZ1 —

10 months 2 weeks ago

Secondary menu

Copyright © 2024 Primary Care Collaborative